Clive James Interviewed by Nichola Deane

This interview took place in the Warwick Arms Hotel in late January 2009. The interview was designed to be a response to Clive James’s Cultural Amnesia, an erudite and accessible A to Z of essays on figures he considers ‘necessary’ to a consideration of ‘history and the arts.’ It is that rare kind of book that makes you want to begin your intellectual journey all over again: both to re-experience first encounters with favourite writers and artists and to attempt to cram in more, much more than you did the first time around. Cultural Amnesia is full of joie de vivre. It is also full of treasure. Although this interview might just as easily have been about Louis Armstrong, Anna Akhmatova or W.C. Fields, I chose to ask Clive James about F. Scott Fitzgerald, because his essay on the author of The Great Gatsby seemed to me to hand the reader a skull-cup full of Fitzgerald’s gusto—and to hint at the wellspring from which it came. As readers of Gatsby and Tender is the Night will know, Fitzgerald’s prose is intoxicating. But even talk of Fitzgerald’s prose is intoxicating, especially when delivered with James’s balance and wit. In other words, James’s Fitzgerald-talk in Cultural Amnesia demanded further Fitzgerald-talk. The talk recorded here doesn’t get close to dissecting Fitzgerald’s talent, but then it wasn’t meant to: ‘talent can be dissected, but not alive,’ James tells us, writing of Fitzgerald. James’s gift as an essayist is in rendering his subjects up to us, living and breathing. He does this in much the same way that a first-rate novelist renders up their characters: through lightness of touch, the bull’s-eye detail, and, of course, cadence. Even in an unprepared interview such as this one, his ability to conjure is in evidence. Fitzgerald’s talent may not be dissected here, but his voice sings out: thanks to James, the beautiful, cracked, leather-lunged engine of that voice rises up out of the mist, on top of the sunshine.

ND: There are two main reasons I have asked to do this interview. They boil down to one elegant essay of yours on F. Scott Fitzgerald in Cultural Amnesia and the fact that the atmosphere in the essay echoes the feeling I have long had for Fitzgerald. It all started before I had even read a word of his, when I watched The Last Tycoon in my early teens. Even though the film wasn’t very good, and it’s Fitzgerald’s least successful book, there was something about it, perhaps in the beauty and sadness of De Niro, perhaps in Elia Kazan’s visual imagery (that half-built Malibu beach-house) that radiated Fitzgerald’s style. Of course I only realised that the tone of the movie was borrowed from Fitzgerald’s prose cadence much later. Nonetheless, the movie put me into a kind of trance. The power of his prose reached beyond his prose. Can you recall the effect that your first encounter with Fitzgerald had on you? Can you locate it to a place or a time?

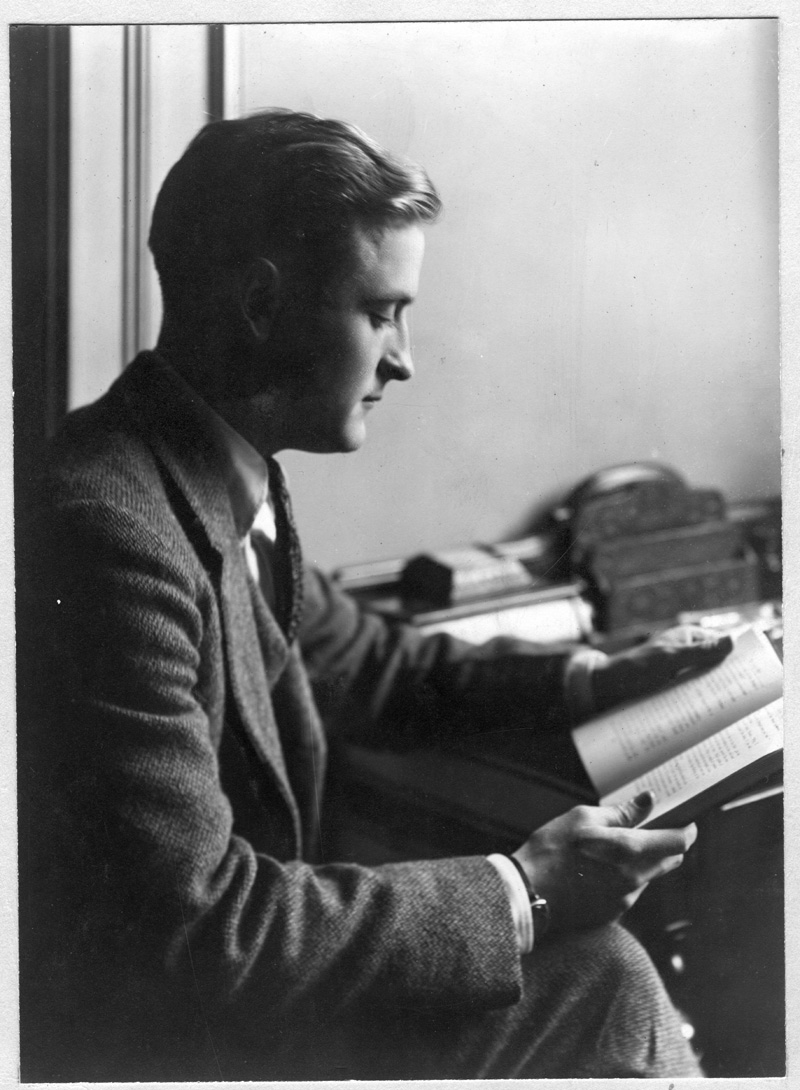

CJ: I can certainly remember my first encounter with the movie The Last Tycoon. The movie is a cripple; it just goes all wrong. I think that Harold Pinter, who wrote the screenplay, was aware of that, and counted it among his regrets. De Niro is simply not straightforwardly elegant enough or eloquent enough to play Monroe Stahr, and the ingénue, Ingrid Boulting, was a disaster. Kazan was in love with her and she couldn’t act. She had a head shaped like a television set, so the actual centre of the movie was a mess. The main guy, who was meant to be godlike in every way, is a mumbler, and there is no reason for the love interest, so thank God I wasn’t meeting Fitzgerald through that movie; thank God I didn’t meet him like that at the age you were. I met Fitzgerald in the 1950s, long before your time, when I read The Great Gatsby, recommended to me by friends at the university. It wasn’t on the course, and I was simply knocked out. To give myself credit, it’s one of the times where I responded the way I was supposed to. First time, no mucking about. Obvious masterpiece. I wouldn’t have felt that way if I was reading The Golden Bowl, for instance, but Gatsby is so convincing on every level, and so engaging on every level, that it gets you straight away. Then I read Tender is the Night.

ND: Straight after?

CJ: Straight after. And then I read The Crack-Up, which is Edmund Wilson’s collection of Fitzgerald’s essays and notebooks, prefaced by that wonderful poem he wrote for Fitzgerald , a poem which I adore. Principally it’s a collection of Fitzgerald’s last essays. So I read them all in a batch. And in a downtown bookshop in Sydney, I found four old pre-War copies of the magazine Esquire, each one of which had an article from The Crack -Up in it, and that little stack of old magazines became one of my most treasured possessions. They were so precious that I eventually gave them to Julian Barnes, because Julian collects these things, and I have no facilities for guarding treasures. What drew me to Fitzgerald permanently, and influenced me profoundly, was his essay style; it was obviously the way to write expository prose. But I don’t think you wanted to ask me just about that, you wanted to  ask me about Gatsby. Gatsby was the first thing, in fact, and as I remember your brilliant question, now that I’ve digressed for so long, it was about how I encountered Fitzgerald. I encountered him though the book of The Great Gatsby. Thank God, not through one of the movies, although one of the movies had already been made with Alan Ladd as Gatsby—very good casting by the way. He was top box office star in the world at the time, and he was great at being enigmatic because he never moved a muscle in his face. But it didn’t save the movie, any more than Robert Redford’s equivalent rigidity saved the later version. So, no, I didn’t see the movie, but I read the book, and I read every word of the book, started memorising lines from the book. I can still do them.

ask me about Gatsby. Gatsby was the first thing, in fact, and as I remember your brilliant question, now that I’ve digressed for so long, it was about how I encountered Fitzgerald. I encountered him though the book of The Great Gatsby. Thank God, not through one of the movies, although one of the movies had already been made with Alan Ladd as Gatsby—very good casting by the way. He was top box office star in the world at the time, and he was great at being enigmatic because he never moved a muscle in his face. But it didn’t save the movie, any more than Robert Redford’s equivalent rigidity saved the later version. So, no, I didn’t see the movie, but I read the book, and I read every word of the book, started memorising lines from the book. I can still do them.

ND: Can you give me a couple of examples?

CJ: Well, up until recently I could recite the whole last paragraph that ends with the sentence everyone can quote, ‘and so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.’ I could recite the sweep of prose that joins together those unforgettable phrases like ‘Gatsby believed in the green light’, and ‘the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock’. Gatsby believed in the green light. That’s the cadence: he believed in it. It’s not that he believed in the green light, as a symbolic concept of going ahead: he just believed in that green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. I can recite that and some of Nick Carraway’s aphorisms, which are a bit too good; the question does arise of how Carraway manages to keep being so aphoristic. ‘If personality is nothing but an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him…’ Which is a very good thing for a man selling bonds to say, for a guy who is supposed to be flogging merchandise. How come he’s a philosopher? There are a lot of things like that, but it’s a long while since I read it, so you can see memory is doing its work. I’ll read it again soon.

ND: I re-read it recently and everything just seems to go straight into the memory, effortlessly so; it falls on you.

CJ: Yes, it’s got its depth at the surface, which is a wonderful quality, and there’s more depth underneath. If you go back in later life, when you’re much older than you are now, more and more truth will arise from that book. The actual longing in the book is not trivial, [the book is] all the deeper for that person’s longing for someone else. He builds his house or rents it or hires it or rebuilds it or whatever he did, just so he can be near Daisy, as a way of impressing Daisy. The scene with the shirts, where he gets his shirts out of the cupboard…

ND: It’s beautiful, isn’t it?

CJ: That’s one of the great scenes, and it’s a test for any writer to read that scene and figure out how he would have done it. Wouldn’t be done that way now, because we are now in the age of research; novelists tend to want to do research and put it all into their books. Take Salinger: when one of his characters, I think it was Zooey, goes through the medicine cabinet in the bathroom, he names every medicine in it, every cream, every preparation, It’s all researched, and now authors like Don DeLillo…they all do it.

ND: But it’s all about touch, though, how the things feel to the touch.

CJ: Yes…But Fitzgerald didn’t do [research]. Those were good shirts, he wants you to imagine a good shirt as opposed to a cheap one, but if he had named the names, if he had put in the brand names, Turnbull and Asser cufflinks and so on, it wouldn’t be the same. No, it’s just the textures, it is just the finest…Gatsby has got the best stuff, and he thinks that she’ll respond to it, and she does: she says ‘I’ve never seen such beautiful shirts before.’ Well, she probably has, she’s married to a rich man; Tom’s got those things too, but Gatsby loves them. What a scene!

ND: The whole thing is about the sense of touch though, isn’t it? It’s the two of them passing the shirts between them.

CJ: Yes. It’s a way of dancing. Fred and Ginger would have danced it, although nowadays it would have been a bedroom scene.

ND: But his prose feels like dancing, all the time. Every single word of it. You end the essay with that lovely phrase ‘the style was the man.’ I’d like to get closer to Scott the man first of all, by trying to think about how you would interview him if I could somehow arrange for him to walk into this room, now. Firstly, if we had the luxury of choice, when in his life would you like to talk to him?

CJ: Well, he would probably stagger into this room, because one way or another he was always drunk. He was an alcoholic and it showed up as soon as he got to Paris when he was quite young, in the great days of Fitzgerald and Hemingway as the two young stars on their way up. In Paris, Fitzgerald was already a drunk. He would have been a drunk back in New York. He had a light head, which is what stopped him dying early. With a hollow leg he wouldn’t have lasted ten years. As it was, his light head made sure that he passed out before too much damage was done to his brain, but he never could handle alcohol, and you can tell he wouldn’t be able to by the way he talks about the Ring Lardner character in Tender is the Night. He makes the Ring Lardner character the drunk, which indeed Ring Lardner was. Lardner was a controlled drunk. Fitzgerald was passing off his own affliction as someone else’s affliction— and he had a real affliction. A time to interview him would have had to be fairly carefully chosen,  maybe in his last phase when he thought he was sobering up, which meant he was only drinking beer. He really thought he was on the wagon if he drank just beer. So, maybe then, about the time he was writing The Crack-Up. Reading The Crack-Up is an answer, a long answer to an interview. The question is: ‘How are you feeling?’ And ‘If you looked back on your past, would you do anything different?’ And he would have done everything different. He probably wouldn’t have written The Great Gatsby. The point of my essay is there’s no unbroken version of Scott Fitzgerald. There’s probably no unbroken version of any man. It’s just that his breakages were right there, they were the source of his inspiration. But I would love to have heard him talk. I’m not so sure he did all that much listening; at the time. He would store things away: a notebook writer, he would remember phrases and so on, but he was always…

maybe in his last phase when he thought he was sobering up, which meant he was only drinking beer. He really thought he was on the wagon if he drank just beer. So, maybe then, about the time he was writing The Crack-Up. Reading The Crack-Up is an answer, a long answer to an interview. The question is: ‘How are you feeling?’ And ‘If you looked back on your past, would you do anything different?’ And he would have done everything different. He probably wouldn’t have written The Great Gatsby. The point of my essay is there’s no unbroken version of Scott Fitzgerald. There’s probably no unbroken version of any man. It’s just that his breakages were right there, they were the source of his inspiration. But I would love to have heard him talk. I’m not so sure he did all that much listening; at the time. He would store things away: a notebook writer, he would remember phrases and so on, but he was always…

ND: I haven’t looked much into the notebooks; did he write them copiously?

CJ: He did, and some of it is just ideas for books. He worked the opposite way to Hemingway actually. He could have developed anything into a book, Fitzgerald. But with Hemingway you often wish he hadn’t. Fitzgerald was a great note-taker, and had a great ear, but I think in conversation he wouldn’t have been much of a good listener. And I’m not so sure if he was alive now the whole business of being interviewed, being a celebrity, would have suited him at all. For one thing, he was too much of a snob. He liked the social high life. He was more like Cole Porter than he was like a contemporary writer. He’d be fascinating from a distance. People used to avoid the Fitzgeralds. They were a terrible joke in New York. If you’ve got some new furniture and you want your furniture distressed, ask the Fitzgeralds over for dinner. If you had a new sofa, Fitzgerald would probably vomit on it.

ND: Do you think you could have been friends with him? Do you imagine that you could have been?

CJ: I can’t imagine myself being friends with any famous writer, actually, or they with me. They wouldn’t find me interesting enough. I spend a lot of time brooding. I would have loved to watch him in action. If he could have just stayed alive long enough to see his contemporaries at their worst it would have been quite fun. Any writer who stays alive long enough will see some of his famous contemporaries in a moment of weakness. I could give you a catalogue: I’ve seen Lowell making a beast of himself. It didn’t stop him being a great poet. He stopped himself being a great poet eventually, but behaving like a beast wasn’t what did it. Larkin I met several times, in fact Larkin I knew. But being friends with him, that’s a different question. I don’t see myself being friends with Fitzgerald, I’m not sure he would have wanted it.

ND: Do you think he had real friends then?

CJ: No, it was just social friendship. He believed in Society with a capital S, and the Fitzgeralds were the kind of people who ruined the Riviera. After Harry and Caresse Crosby built their house at Antibes, people started to come to the south of France for the summer. When the Fitzgeralds pitched up that was the sign it was turning into high society. Picasso got there before that. Picasso was careful to leave when that happened, and actually I think Fitzgerald modelled the character of Dick Diver partly on Crosby. The American abroad, the suave man who wastes his gift by just running the scene for the benefit of others… Fitzgerald was never sober enough to run the scene. He would arrive late and leave early, or arrive late and leave never, or leave in an ambulance.

ND: [laughs] Carried out.

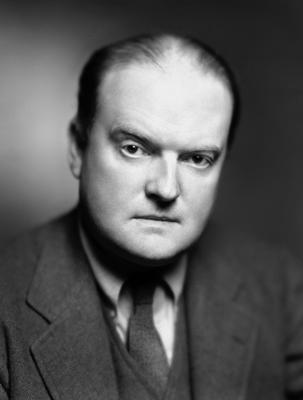

CJ: After failing to extract Zelda from some hopelessly compromising situation. But in his own mind, he was a social catch, very handsome.

ND: He looks like a movie star.

CJ: Oh sure, he had the kind of profile that’s in profile even when he’s looking at you. That nose is magnificent. But I think the current age of celebrity would have struck him as too cheap. For him it was always mixed up with the real high life: ‘The rich are very different from you and me.’ He didn’t really mean that. The bit he really meant was they have more money. It was a great tragedy for him that he had no gift for money. He could earn it but he couldn’t keep it. Financial probity is a talent and he didn’t have it.

ND: How would you sum up Fitzgerald’s personality? Is there a poem —you mention Wilson’s ‘Scott, your last fragments’ in your essay— that might do this?

CJ: Wilson looked up to Fitzgerald’s natural talents but looked down on him as a mind, which was an unreal division, in my view. And anyway, Fitzgerald was never really as unscholarly as it suited Wilson to make out. In his maturity, Fitzgerald read a great deal. When he told his daughter that had hundreds of books about Napoleon in his library, he wasn’t kidding. But in Wilson’s mind Fitzgerald was a bad student because Fitzgerald had been a bad student when they were in college at Princeton.

ND: You get an image of what a person is like when they are young and you can’t let go of it.

CJ: Yes, and this is why you have to get away from your friends. At some stage you have to leave, or the people that know you will trap you in an image, and as far as Wilson is concerned, Fitzgerald was the talented goof-off, and of course he was, compared with Wilson. At Princeton they were both students of Christian Gauss, the great teacher. Certainly in Wilson’s eyes, Fitzgerald was the brain that could have been fine but never applied itself. Well, Fitzgerald never stopped applying himself all his life, and luckily he got away from Wilson. All the writers were lucky if they got away from Wilson because he would trap them in his impression of them, which was very, very sharply defined and very well done and everybody listened. Hemingway got lucky with Wilson, for example, but Nabokov eventually rebelled against him. It’s the Dr Johnson role. Wilson did treasure the Fitzgerald masterpieces. I think he called them two diamonds, Gatsby and Tender. I think he said that Gatsby was the perfectly cut one and Tender was the half-cut one, which is about right. Certainly he valued Fitzgerald as a prose writer, but he always gave the impression that he thought that with Fitzgerald it was a kind of fluke. It’s the way the Australian sports reporters used to talk about the swimmer Dawn Fraser. They would dismiss her genius on the grounds that she was a natural swimmer.

ND: She didn’t have to work at it, apparently. Although of course, with people like that, all the work is hidden. Fitzgerald said Edmund Wilson acted as his literary conscience. It strikes me from reading your essay that Fitzgerald acts as a stylistic conscience for you.

CJ: Well, I think Fitzgerald was sucking up, and there’s something to it. Wilson certainly disapproved of Fitzgerald being involved in Hollywood in any way, and someone who can’t manage money should never have been involved in Hollywood. But Faulkner could strike the balance. He used to spend half the year in Hollywood. That’s how he made the money to stay alive, so he could write unsaleable novels about Yoknapatawpha County. Those novels would not have existed on paper if Faulkner had not spent half the year in Hollywood writing screenplays. But Faulkner knew how to do just so much for his paymasters and keep the real energy for his own artistic purposes. Fitzgerald always  had this fatal habit of practising the screenplay as an art-form, and Hollywood had no intention of letting that happen. Hollywood was a business and at his best Fitzgerald spotted it. Monroe Stahr is one of the few people who is capable of holding the whole equation of movies in his mind. The equation of course included business and practicality and the necessity to fire a writer or hire a writer and not tell the first writer. Fitzgerald was always being fired from a movie and finding out afterwards. Fitzgerald would commit his whole talent to worthless screenplays and then be devastated when the work wasn’t used. There’s a wonderful interview with S.J. Perelman for The Paris Review—Perelman was my favourite New Yorker writer, a big influence on my work actually. And Perelman was there in Hollywood at the time and he said that Fitzgerald was fatally, fatally incapable of realising what was involved when he was being used as a writer. He didn’t realise what the deal was, he just didn’t get it. He was an artist lost in a business.

had this fatal habit of practising the screenplay as an art-form, and Hollywood had no intention of letting that happen. Hollywood was a business and at his best Fitzgerald spotted it. Monroe Stahr is one of the few people who is capable of holding the whole equation of movies in his mind. The equation of course included business and practicality and the necessity to fire a writer or hire a writer and not tell the first writer. Fitzgerald was always being fired from a movie and finding out afterwards. Fitzgerald would commit his whole talent to worthless screenplays and then be devastated when the work wasn’t used. There’s a wonderful interview with S.J. Perelman for The Paris Review—Perelman was my favourite New Yorker writer, a big influence on my work actually. And Perelman was there in Hollywood at the time and he said that Fitzgerald was fatally, fatally incapable of realising what was involved when he was being used as a writer. He didn’t realise what the deal was, he just didn’t get it. He was an artist lost in a business.

ND: I like him for the fact he didn’t get it.

CJ: But he had to do it: he had the remains of a family to support, Zelda’s endless bills to pay, and he was a responsible man about money, it was just he had no control of it. He should never have earned any big money in the first place, but then we never would have heard of him. Zelda is a problem in herself which we will get round to…

ND: The second half of my question was if Wilson acts as a literary conscience for Fitzgerald, does Fitzgerald act as a stylistic conscience for you? I suspect he does, and if so, how?

CJ: There are many consciences operating inside, not all of them writing in English, but Fitzgerald is certainly one of them. I wanted my prose to sound that easy, that effortless to read. That was a sine qua non. But he wasn’t the only one who taught me that. There were quite a lot of Americans. Dwight Macdonald was one of those people who could write this clear prose. In English, the great exemplar was Bernard Shaw. Nobody affected me like Bernard Shaw, but it doesn’t show in my writing. I read the whole thing, early. I read the six volumes of criticism, that’s three volumes on theatre and three volumes on music. The six volumes in the standard edition I practically memorised, and I did all that before I left Australia. I absorbed it and it doesn’t show, but the ideal is there.

ND: But do you feel that Fitzgerald shows in your prose writing?

CJ: I hope not. I hope nobody does. I hope it’s all me. I quote people right and left, but the basic thing is me. There might be a congruence of attitude, though. He’s very, very good at regret, and I do a lot of regretting. I wish the past was different, I wish the life of my family, my mother and my father was different. A lot of that gets into my prose, and I hope I caught some of that from The Crack-Up. The Crack-Up made me realise that it was possible to write about your own interior drama. I do nothing else. All my work is about my interior drama, with these cardboard characters stumbling about, and there’s no point being ashamed of it, that’s the way it is. I think I probably learned some of that attitude from Fitzgerald. I wouldn’t be happy to hear that I’d actually borrowed his tone or anybody else’s. One hopes to have one’s own tone by reading everybody’s tone, not just one person.

ND. Of course.

CJ: It’s very bad to be enslaved by one writer. I knew a wonderful young poet in Australia when I was young, named Richard Appleton. He was terrifically gifted. He worshipped Ezra Pound. The trouble was he worshipped Ezra Pound and nobody else. He didn’t read anything else. There’s no point doing that. But I think I dodged the question. If you say I sound like Fitzgerald I would say thank you, but no thanks.

ND: That wasn’t quite what I meant. Actually I wanted to get closer to Fitzgerald’s style really, and maybe a bit closer to yours. I don’t mean to suggest some kind of transfer of technique, more like ‘what does he make you realise or see about writing or life?’ ‘What does he make you more true to?’ A conscience trues you somehow, straightens something out in the heart or the head--or it complicates you in a useful way. On the theme of conscience though, what do you think Keats does for Fitzgerald? You say a little about this in the essay, and I would just like to hear you speak a bit more about that.

CJ: It’s a good question. I think your opinions will probably be better than mine. Fitzgerald obviously loved the poetry. The choice of Tender is the Night as a title for the big novel, is, as the academics would say, no accident. Already there is a lovely start to the line. Obviously the cadences of Keats, especially the Odes, are important. He had a sense that the Odes are beautifully cadenced. Above all they’re prose constructions on a high level. They’re prose constructions that are poetically arranged, poetically charged, but the argument is clear throughout, as Fitzgerald’s argument always was. It’s not so much that he decorates but that all the decoration contributes to the architecture. Fitzgerald’s prose is poetic in that sense and he copied a lot of that from Keats and the other poets, including the mystery poet Thomas Parke D’ Invilliers who is quoted at the start of The Great Gatsby:

Then wear the gold hat if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry ‘Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!’

Thomas Parke D’Invilliers was Fitzgerald. He invented a poet. I think he would have liked to have been one. I think he had enough sense to realise he already was one, in his prose. But the direct connection between him and Keats? Well, I think he knew the letters really well, and he must have often thought what if my life had been cut short, what would I have achieved? That’s a very good reason for being a young man in a hurry. Most of the reasons for being a young man in a hurry are very bad reasons. The good one is if I can achieve renown. How old was Keats when he died? Twenty-six?

ND: Twenty-five.

CJ: But I am going to have to leave direct connections to you…

ND: As far as I can see, there is a shared smoothness of style. And I’m not attempting to suggest that Fitzgerald learned that from Keats, more that there’s an attraction to Keats because Keats talks that way naturally and so does Fitzgerald. But it’s not only smoothness, there’s also that love of sensual excess. The shirts episode in Gatsby reminds me of the feast that Porphyro sets out for Madeleine in The Eve of St Agnes. Fitzgerald’s shirts and Keats’s food, the ‘lucent syrups tinct with cinnamon,’ are jumping-off points, a way of gesturing towards unquantifiable feelings and desires. These little trifles show you where the big heart of the work is, but they leave that heart a few steps beyond you. Both Keats and Fitzgerald are great at leading you to an abyss of feeling, only to demonstrate that the feeling is beyond anyone’s reach. Porphyro and Gatsby are left helpless when faced with these feelings, and so are we. But just in terms of style really, the way things melt, that melting, dissolving thing. That’s one of the key things that struck me when reading Gatsby anyway. It’s so fluid in the way that Keats is.

CJ: Well, Keats’s’ prose in the letters is ideal prose isn’t it? And I suppose the ideal prose, the ideal prose of one writer talks to the prose of another.

ND: It’s about proximity. When you read a letter of Keats’s, he is in the room with you. He’s so present.

CJ: That’s what we all want but some of us can’t do it [laughs]! Everybody wants a bedside manner. He’s certainly got that.

ND: If you were to write another essay on Fitzgerald, what would you want to focus on?

CJ: I would probably talk about Gatsby, and talk about everything I noticed about Gatsby. But I would like to write a short essay about the obvious things. I would like to write something that would make it compulsory to go and read The Great Gatsby immediately. And the question is what would you choose? Well, some of his fellow writers, especially the New Yorker writers, commended him for the attention he gave to the guest-list at Gatsby’s party. That was a sort of catalogue scene. The so-and-so’s were there and the so-and-so’s were there and they were driving so-and-so. Or the wonderful, wonderful scene where Gatsby is talking to Nick, and I think Nick says that Daisy was really in love with Tom and Gatsby says this terrible, terrible thing. He says that ‘it was just personal.’ That scene says everything, because in Gatsby’s mind, merely personal love between people is nothing compared to the Platonic love— Platonic in the sense of ideal and vast— that he has. And that was all done in about two lines. Fitzgerald’s economy I would try to bring out. Actually, being extravagant in praising someone’s economy is a bad way to praise it. I would be economical in my praise. I wouldn’t go in search of hidden treasures in the short stories.

ND: I love that bit where Nick’s walking around and into Tom and Daisy’s house; they walk through the garden, into the house and they see Daisy and Jordan Baker sitting on a sofa and they’re floating. It’s as though the garden comes into the house and the women are just off the ground.

CJ: And the garden, the lawn goes round the house like a river, flowing away. Somebody picked out—I think it was Dwight Macdonald, or it might have been Dorothy Parker—picked it out as something that nobody else can do. Yes, Daisy and Jordan floating. I remember that bit. Of course I remember Jordan, because Jordan is there as a reminder of how anchored Fitzgerald could be about human character.

ND: The Nick and Jordan relationship doesn’t ever seem to get off the ground.

CJ: Well, she’s trouble, and Nick has moral objections to Jordan. The question is how many moral objections do you have to an attractive woman who wants to sleep with you, and the answer is they usually come later. Here they seem to come earlier, at the moment when Nick hears the rumour about how Jordan moved a golf ball. Jordan cheats at golf. Not the gentlemanly thing to do, and yet she is a gent, she is completely at ease in those circumstances, a parvenu with style. Jordan is one of them. She’s there to prove to Fitzgerald that he’s anchored in the real world, and all that idealistic stuff is part of the real world too, although he could have left it just at including Tom’s mistress. Tom’s mistress is sufficient to do that. She’s low rent, she lives in this knock-down place on the way to the Valley of Ash. There’s a thing you could quote—gems from Gatsby—about the pair of spectacles above the ash-tip.

ND: It’s such a weird image but it’s brilliant.

CJ: I think T.S. Eliot pinched it. I think it’s somewhere in The Waste Land. He knew a lot of Fitzgerald early. He sent Fitzgerald a letter saying that ‘your book is the first advance of the novel since Henry James’ and later on when Gatsby and Tender is the Night were published by Penguin in England, a quote from that letter was used on the cover. It isn’t any more, but someone very correctly saw that this endorsement is worth something. Eliot was struck by the Valley of Ash as a weighty symbol, quite obviously, and for Fitzgerald it probably just came naturally. Between the house in New York and the house in Long Island he went through the Valley of Ash, sure. But it’s the spectacles [on the billboard] and, oh, the man who fixed the World Series. One of the greatest scenes in all literature [laughs]. The way that’s integrated; Fitzgerald casually mentions that he fixes the entire World Series.

ND: You have to read that twice …

CJ: There really was a guy who fixed the World Series and Fitzgerald probably knew him. He would appear on the social scene. He was well known, this one guy. But the novel is just so rich; for such a small space. It’s short, a bonsai novel, as Nichola Deane would say. But it all fits, which brings you to Tender is the Night. Is Tender is the Night really bigger and more ambitious or is it simply less organised?

ND: I don’t think that the added size of the novel makes it more ambitious than Gatsby. Gatsby’s ambition resides in its compression. Tender is not as ambitious as Gatsby because, although its scope is broader, it doesn’t quite have Gatsby’s hyper-concentrated strangeness. The ambition is evident in that sense of unwavering, painful concentration. There are no floating women in Tender is the Night. However, I’m not sure that Tender is less organised than Gatsby: there is still that marvellous arc up to perfection and down again into disintegration. But as far as you are concerned, are there any flaws in Tender is the Night?

CJ: There are. There’s something about the way that the writer in Fitzgerald presents Dick Diver. Although Dick Diver is allowed to decay in the end, it’s obviously the depiction of an ideal that Fitzgerald would like to be, and there’s a bit of a falling-short. Somewhere in the centre of the novel, there’s a wish-fulfilment character and I think it’s Dick Diver. And he always knows what’s right and what to do. He can even handle Nicole, and only at the end does time catch up with him and he falls off the waterski or whatever it is, a moment that I think of increasingly often as I approach the later phase of my life. Somewhere in there, in the actual character of Dick Diver, is the problem with Tender is the Night. Everything else that attaches to it attaches beautifully. The spine is strong, and the incidental characters, such as, say, Tommy Barban. Nicole herself is wonderful.

But how obvious is it, that flaw? It is a problem because we start to find out about the writer and we tend to know  about Scott and Zelda before we read Tender is the Night and it affects our judgement. I read the book before I knew about Scott and Zelda and I still thought that there was something wrong with the book. Who was this guy who just wanted to live well? He was the king of Antibes. Who wants to be that? I’ve met the king of Antibes, the guy who is king of the beach, who knows the best town to drive to if you want to get the best prawns cooked in salt. I knew several of them. Most of them had known Hemingway and not Fitzgerald and it’s a boring thing to want to do. Dick is so obviously a man who wanted to be an artist but can’t, so he makes art out of his life.

about Scott and Zelda before we read Tender is the Night and it affects our judgement. I read the book before I knew about Scott and Zelda and I still thought that there was something wrong with the book. Who was this guy who just wanted to live well? He was the king of Antibes. Who wants to be that? I’ve met the king of Antibes, the guy who is king of the beach, who knows the best town to drive to if you want to get the best prawns cooked in salt. I knew several of them. Most of them had known Hemingway and not Fitzgerald and it’s a boring thing to want to do. Dick is so obviously a man who wanted to be an artist but can’t, so he makes art out of his life.

ND: But it’s so fragile, that life.

CJ: Well maybe he’s telling us that it’s not enough. For vast stretches of the book you think that this guy is a hero. I think he would be regarded by anyone looking at him objectively from here as just another drag.

ND: The problem is when he ceases to be a hero, he amounts to less and less and less and it feels like the book is dribbling away from you.

CJ: It’s already doing that before he falls from the ski and sinks back into America. Yes, it does tail off. When you think about it the book tails off from the start. On the other hand, there are stretches of it that you could never get over. I sometimes feel that about Rosemary Hoyt. Is Rosemary Hoyt the one in Tender?

ND: She’s in Tender. She’s the eighteen-year-old starlet.

CJ: She’s the starlet and she loves Dick, and it’s her first grand passion, and she catches the first hint of how grand it could be when Dick and Nicole get hot for each other in front of her. Where are they?

ND: They’re near the phone booth in some hotel or other.

CJ: And she hears it and she realises what’s going on. A grown-up love which she is just approaching, and she must have Dick Diver. But she’s superbly drawn as Fitzgerald’s dewdrop. Fitzgerald’s dewdrops are his favourite characters. They’re in The Last Tycoon too. Rosemary is very believable.

ND: He doesn’t seem to be very distant from them either. It’s as if he is them. Think of that scene when Rosemary overhears Dick and Nicole—I like the idea that he doesn’t seem to be really separate from his female characters.

CJ: It’s a strong point that he had an unusual insight into his female characters. It’s the kind of thing we start expecting from gay male writers or filmmakers. Almodovar, for example, has an incredible insight into women, and you think only men who are half-women can do this. I think Fitzgerald was fully butch, but he did have an unusual sensitivity, I’m told, to the way women would react. Most men need telling how women would react. Most men need telling how men would react.

ND: But that’s Keats again, taking as much delight in an Iago as an Imogen. That’s why Fitzgerald is a genius as far as I’m concerned, because he could do that. He doesn’t seem able to separate himself from people like Rosemary. There are no walls in Fitzgerald.

CJ: You can see everyone is transparent.

ND: Think of that bit in Gatsby where Nick is walking round the house and Daisy and Gatsby are off in another room somewhere. Nick is listening for the sounds they make and they’re not making any sound. But at the same time you feel you are able to go through the wall to where they are, beyond where Nick is.

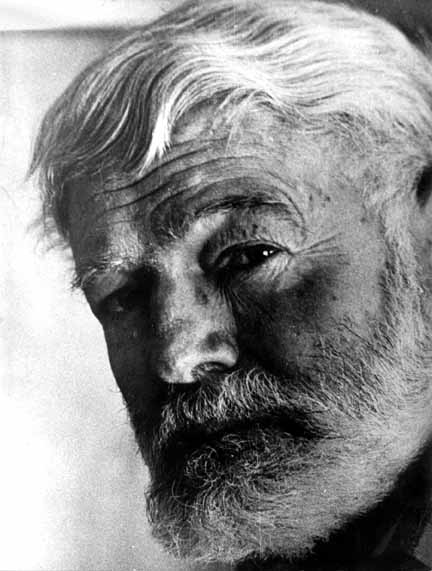

CJ: He does a pretty good job of solving the question of how much the narrator knows in Gatsby,  but in Tender he has more freedom. Tender wants to be an epic of fiction. Gatsby is big but it wants to be big in a small space. Tender… maybe I should read it again. Hemingway himself said it’s amazing how much better Tender is the Night gets as you go on reading it.

but in Tender he has more freedom. Tender wants to be an epic of fiction. Gatsby is big but it wants to be big in a small space. Tender… maybe I should read it again. Hemingway himself said it’s amazing how much better Tender is the Night gets as you go on reading it.

Hemingway went on reading Fitzgerald. He knew Fitzgerald was good, that’s why he tried to knock him down. Hemingway was a viciously competitive character, a very nasty one in many ways, but a great judge of writing, and he knew Fitzgerald really had the gift.

ND: Both of those books seem to have that power. I can see myself re-reading them now and again for the rest of my life.

CJ: Well, both came close to being perfectly finished. The reason I don’t much like The Last Tycoon is that I don’t think the pot was thrown. It’s not even that the pot doesn’t have its final glaze, it’s that the book is a wreck. He was probably on the wrong subject, admiring a representative of the system that was wrecking him; he wasn’t ready to carry that through and explore the full implications of this powerful character. Monroe Stahr is the kind of character who would eat writers like Fitzgerald for breakfast.

ND: Squash him.

CJ: Squash him.

ND: The last thing I want to do, as a closing tribute, a glass raised to Fitzgerald, is to read through a short passage from Tender is the Night and to talk through what is great about it. I love this little bit. I have a copy of it here, actually.

CJ: You’ve got it? Should I read it?

ND: Please! You’d read it far more elegantly than I would be able to do.

CJ: Well, I’m reading it cold... [reads aloud the following extract:]

When the funicular came to rest those new to it stirred in the suspension between the blues of two heavens. It was merely for a mysterious interchange between the conductor of the car going up and the conductor of the car coming down. Then up and up over a forest path and a gorge—then again up a hill that became solid with narcissus, from passengers to sky. The people in Montreux playing tennis in the lakeside courts were pinpoints now. Something new was in the air; freshness—freshness embodying itself in music as the car slid into Glion and they heard the orchestra in the hotel garden.

When they changed to the mountain train the music was drowned by the rushing water released from the hydraulic chamber. Almost overhead was Caux, where the thousand windows of a hotel burned in the late sun.

But the approach was different—a leather-lunged engine pushed the passengers round and round in a corkscrew, mounting, rising; they chugged through low-level clouds and for a moment Dick lost Nicole’s face in the spray of the slanting donkey-engine; they skirted a lost streak of wind with the hotel growing in size at each spiral, until with a vast surprise they were there, on top of the sunshine. (Book II, chapter ix.)

CJ: The miracles that you give me here. Isn’t that miraculous?

ND: Just unbelievable. The bit where Nicole turns up with this boyfriend…

CJ: Tommy Barban?

ND: I don’t think it is Tommy Barban.

CJ: He’s a bad-news-boyfriend.

ND: It’s an early boyfriend anyway, and it establishes that she has left the hospital. The two of them clamber through the funicular car towards Dick. Prior to that, you’ve had the roses coming through the window of the compartment. You’ve already had sensual overload with the Dorothy Perkins roses and then you come to this.

CJ: I don’t think he would have wanted to have charged his prose poetically any more than that. In other words, the reason he didn’t write poetry was that this was a good-enough opportunity for him to put poetry in exactly where he wanted it. It was intended not so much an illustration as an intensification of the description. ‘Between the blues of two heavens,’ for example, is a line from poetry, laid out on the page like a treasure. As you read you want to stop, but you can’t stop because you go on. It’s the ideal impetus of prose: boy that was good, what comes next? The technicalities of the funicular are spot on, of course. He is a notebook writer in that sense. He would have written down ‘leather-lunged’ and ‘donkey-engine.’

ND: There’s lots of clunk going on here as well. It’s not all smoothness. You’ve got a lot of gorgeous stuff happening but…

CJ: It’s all engineering. It’s all built.

ND: It’s a machine, too, this prose.

CJ: And mankind intervenes to take us up through all this beauty. Otherwise experiencing it like this would be impossible. The forest paths of the gorge would have been impassable except on a mule. ‘Solid with narcissus’ is good. ‘The people in Montreux playing tennis in the lakeside courts were pinpoints now’ is not over-emphasised. He could have reached for another metaphor, but ‘pinpoints’ is enough. It might almost occur to anyone. But he actually wants you to see that picture.

ND: But also the little human activity is just being left behind in this vast blazing moment…

CJ: This ascent, this heavenly ascent. ‘When they changed to the mountain train, the music was drowned by the rushing water from the hydraulic chamber.’ You can see him writing down ‘hydraulic chamber’ thinking ‘how does this thing work? It works by a hydraulic chamber.’ The ‘leather-lunged engine;’ I love that. Has it got leather lungs we ask ourselves? Probably not.

ND: I suppose he’s getting at the wheezy sound of the engine.

CJ: We don’t know exactly what it evokes, but it evokes something very specific. It sounds as though ‘low-level clouds’ is brilliantly easy. He knows when to keep it tight. ‘They chugged through low-level clouds’ is all you need to know. ‘Low-level clouds.’ Simple. What’s happening? Well, they’re rising up and the clouds are down here. A simple picture and that’s enough. He loses Nicole’s face…

ND: But then you realise that he’s been watching her the entire time and it’s the shock that I like, the jolt you feel when you see this.

CJ: I’ll give you points for spotting that. That’s how we know he’s looking at her, when the narrator says suddenly that ‘and for a moment Dick lost Nicole’s face in the spray of the slanting donkey-engine.’

ND: But we’ve been distracted by looking at all the scenery, and not at her face. He is looking at it.

CJ: Yes, he is, and he loses it ‘in the spray of the slanting donkey engine.’ You can seen him writing down ‘donkey engine—slanting.’ That’s just terrific. It’s only just then you realise he’s been fixated on her. He’s probably been missing all this other stuff. ‘They skirted a lost streak of wind.’

ND: That’s a wonderful phrase.

CJ: Well, what happens there? It’s a puff of air with the hotel growing in size, ‘growing in size at each spiral, until with a vast surprise they were there, on top of the sunshine.’ ‘On top of the sunshine’ is fabulous. In fact, it’s another title, isn’t it? A lost book by Scott Fitzgerald. The awful thing about it, the really terrifying thing for other writers, is that he could do something so good just like that. Your tape recorder can’t see me snapping my fingers. For him it seems easy. It’s not: it was carefully constructed and took a long time but he could do it; it was well within his capacity. Writing within your capacity is the whole secret. His capacity was vast. He had stuff to burn, and so he used it quite sparingly.

ND: There’s absolutely nothing overdone here. Everything is so hypnotic: the sense of you being taken up somewhere as if in a dream but almost not knowing it is happening.

CJ: I think your insight into it was better than mine. You spotted the main thing, where all that’s going on, and the narrator is seeing it, but his character is watching the face of his adorable, crazy wife. That’s the trouble: we can’t help now seeing Nicole as Zelda. Of course, two whole generations have gone by since I first read this book and Zelda became an icon at one stage for feminism, an example how female talent can be crushed by a male, although I think, by now, common sense has been restored.

ND: You mean something like the Plath and Hughes situation?

CJ: Exactly. But Zelda was the tragedy in every sense. For one thing, she really was schizophrenic. There is such a thing and you don’t have to be driven there. It’s a separate question and a huge topic. For next time.

*For further Fitzgerald-talk, especially on the Dorothy Perkins roses episode in Tender is the Night, see my bonsai essay at Casket of Dreams.