A few articles have appeared in the press recently implying that Australian films would benefit if more adaptations were made from acclaimed literary works. Comparisons are inevitably made with foreign films, particularly English and American, where various eminent authors of those countries have had their works adapted to the screen.

A few articles have appeared in the press recently implying that Australian films would benefit if more adaptations were made from acclaimed literary works. Comparisons are inevitably made with foreign films, particularly English and American, where various eminent authors of those countries have had their works adapted to the screen.

Probably a majority of English language films are adaptations of novels. Many of these would not be based on literary successes but, rather, on popular fiction. But it isn't surprising, at least to me, that a number of writer/directors prefer to eschew adaptations and film their own original screenplays. Many are considerable artists and are reacting to the society in which they live. They prefer the comments, the attitudes, in the films to be their own and not a retread of some other writer's ideas, stories or characters.

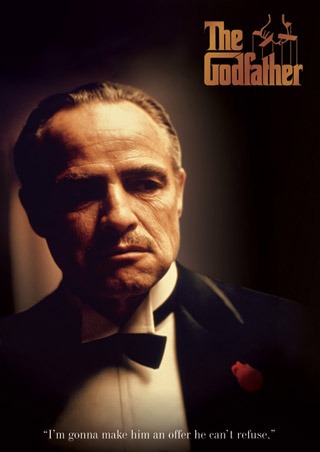

In any event, with adaptations there is usually little correlation between the standard of the original work and the film derived from it. The Godfather, one of the greatest of all American films is adapted from a novel by Mario Puzo widely considered to be a potboiler, while a recent adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter resulted in a risible film.

It's worth pointing out that there is no intrinsic reason why literary-film adaptations should be particularly successful, or why a high proportion of "quality" novels should even be suitable for transcription to another medium. Many novels are famous for their prose style, colorful characters, themes and so on: factors which can obscure the absence of other useful ingredients, such as a coherent plot.

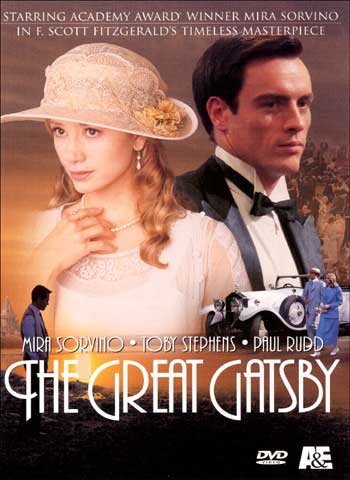

In a film, most of the characteristics that distinguish a literary work are stripped away, and this can reveal the lack of a well constructed story, or convincing dialogue — and be fatal. Almost all of the adaptations of Hemingway novels have been extraordinarily dull. The delicate mood of Scott Fitzgerald's works has not been captured on screen, though the slight plot lines have been all too apparent. The Great Gatsby — so widely admired, such a fascinating novel — has been filmed four times, every version a disaster.

In a film, most of the characteristics that distinguish a literary work are stripped away, and this can reveal the lack of a well constructed story, or convincing dialogue — and be fatal. Almost all of the adaptations of Hemingway novels have been extraordinarily dull. The delicate mood of Scott Fitzgerald's works has not been captured on screen, though the slight plot lines have been all too apparent. The Great Gatsby — so widely admired, such a fascinating novel — has been filmed four times, every version a disaster.

England has fared somewhat better, especially in adaptations of juicy and exuberant Victorian novels, often for television. Many of the films of the Dickens novels have been quite outstanding, despite the film medium laying bare Dickens's quite inept plotting, with its reliance on coincidence for resolutions. Jane Austen, needless to say, has been a continued and resounding success. The BBC does a new version of Pride and Prejudice every three or four years.

From the film-making viewpoint, twentieth century English authors have had mixed success. There have been acclaimed and quite delightful adaptations of E.M. Forster's novels. I particularly admire A Room With a View, directed by the the American James Ivory (who also did a fine version of Henry James's The Golden Bowl), but I thought David Lean's much admired A Passage to India far less successful because the essential ambiguity of the novel couldn't be captured in images, which are notoriously unambiguous.

The satire and dry cynicism of Evelyn Waugh hasn't transferred well to film either, apart from the TV version of his one more or less conventional narrative, Brideshead Revisited. The film of A Handful of Dust, for example, never betrays the fact that it is adapted from one of the great comic novels. Scoop and The Loved One bit the dust in a similar manner. Only Stephen Fry's Bright Young Things, based on Waugh's Vile Bodies captured the feeling of the original.

Looking through a list of the large number of Australian films made since the 1970s, it doesn't seem to me that Australian film makers have been ignoring the works of celebrated Australian authors. Admittedly only one film has been made from a story by the most eminent (and I think the greatest) of all Australian writers, Patrick White: The Night, the Prowler, scripted by White and directed by Jim Sharman in 1977. It wasn't a huge success. No other White adaptations have been attempted. This may be partly because he has been forgotten by today's readers, as many have argued, but I think it's mainly because his novels, like those of Joseph Conrad, whom White greatly admired, are psychological studies, intense and profound and not easy to transfer to a film script.

Looking through a list of the large number of Australian films made since the 1970s, it doesn't seem to me that Australian film makers have been ignoring the works of celebrated Australian authors. Admittedly only one film has been made from a story by the most eminent (and I think the greatest) of all Australian writers, Patrick White: The Night, the Prowler, scripted by White and directed by Jim Sharman in 1977. It wasn't a huge success. No other White adaptations have been attempted. This may be partly because he has been forgotten by today's readers, as many have argued, but I think it's mainly because his novels, like those of Joseph Conrad, whom White greatly admired, are psychological studies, intense and profound and not easy to transfer to a film script.

It's difficult to imagine anyone trying to tackle the complexities of White's Voss, Riders in the Chariot or even the simpler The Aunt's Story. Apart from any other factors, the first two — his most acclaimed novels — would require budgets generally well beyond local resources and on film would almost certainly lack the density of the books. They would likely appear to be nothing more than adventure stories dotted with odd characters.

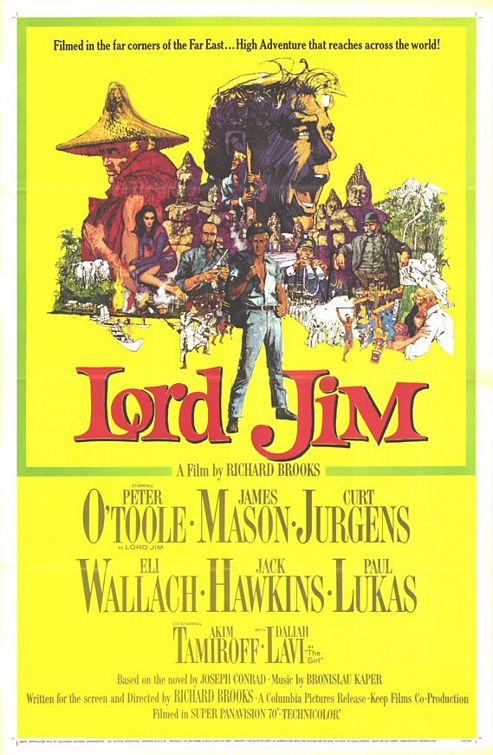

The various film versions of Conrad's novels — Victory, Lord Jim, Nostromo, The Secret Agent — lost all of their subtlety on screen, probably because it was impossible to find a way of capturing the essence of the novels visually. There was no equivalent way to describe Conrad's character insights. Only The Duellists, the Conrad novella turned into a film by Ridley Scott, seemed to me to have the atmosphere and mood of the original story.

Interestingly, some years ago, I think in the late 1970s, the American director Joseph Losey (The Go-Between, The Servant, Accident) spent months in Australia preparing to film Voss. A copy of the script came my way. It read like an Australian western and could have been adapted from a novel by Jack Schaefer or Walter van Tilburg Clark. The film of Voss was never made. I've no idea why, though the main reason films do a last-minute collapse is because all or some of the finance fails to materialize. Anyway, a disappointed Losey returned to England.

Rather than try to build up intellectual credibility by tackling the metaphysics of authors such as White, filmmakers are often better advised to adapt novels which rely primarily on a few strong characters and a compelling narrative. A strikingly successful example of this approach is Canadian director Ted Kotcheff's film of Ken Cook's short novel Wake in Fright. The book won no literary prizes but its story of a schoolteacher in a ghastly outback town was well told, exciting and fast moving. Similarly, many of the novels of the prolific and unacclaimed (by the literary establishment) Bryce Courtenay have been made into successful films and TV mini-series.

Rather than try to build up intellectual credibility by tackling the metaphysics of authors such as White, filmmakers are often better advised to adapt novels which rely primarily on a few strong characters and a compelling narrative. A strikingly successful example of this approach is Canadian director Ted Kotcheff's film of Ken Cook's short novel Wake in Fright. The book won no literary prizes but its story of a schoolteacher in a ghastly outback town was well told, exciting and fast moving. Similarly, many of the novels of the prolific and unacclaimed (by the literary establishment) Bryce Courtenay have been made into successful films and TV mini-series.

The two living Australian writers currently most celebrated by literary critics. and not just in this country but in the world at large, are Tim Winton and Peter Carey. Winton's novels strike me as bargain-basement Patrick White: stylistically derivative, they are far more savage, full of unpleasant characters, and weakly plotted. This view, I should add, is not widely held. I've read a number of Winton novels in an effort to fall in line with so many of my friends and the international critics, but have failed dismally. The two films based on his novels to date, That Eye in the Sky (1994) and In the Winter Dark (1998), were not particularly successful. But Philip Noyce and Ray Lawrence have announced plans to film Dirt Music and The Riders respectively, and a film version of Cloudstreet is also in the works. I hope the last turns out to be a little more concise than the five hour theatrical version of the novel.

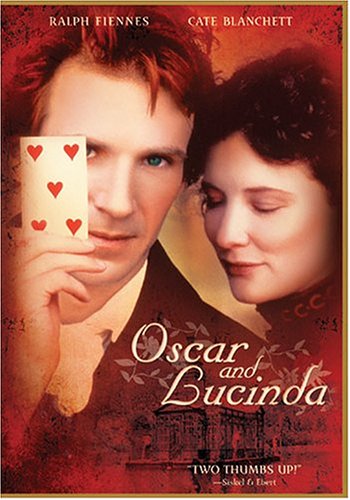

Two of Peter Cary's novels have been filmed — Bliss ( directed by Raw Lawrence) and Oscar and Lucinda (directed by Gillian Armstrong). Both were shown internationally and received critical raves.

Two of Peter Cary's novels have been filmed — Bliss ( directed by Raw Lawrence) and Oscar and Lucinda (directed by Gillian Armstrong). Both were shown internationally and received critical raves.

Fred Schepisi made a powerful film of Thomas Kennealy's The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith. Peter Weir had a huge success with an adaptation of Christopher Koch's The Year of Living Dangerously. Carl Schultz made a delightful film of Sumner Locke Eliot's Careful, He Might Hear You. And the same author's Water Under the Bridge was adapted for TV. The one attempt at a Christina Stead (a turgid writer in my worthless opinion) was Stephen Wallace's For Love Alone, and it was not notably successful. I filmed Henry Handel Richardson's The Getting of Wisdom in 1977. Critics did not share my admiration of the result.

Last year Murray Bail's Eucalyptus came close to being filmed, with a cast that included Nicole Kidman and Russell Crowe, but it collapsed mysteriously a few days before shooting was due to begin.

I could go on giving examples, but this article would descend into a tedious list of titles. The point has been made, I think, that Australian film makers are certainly not unaware of Australian novelists. There are a lot of gifted and determined directors and writers in Australia. I find it impossible to be gloomy about our future. There will be a never-ending stream of impressive films, along with the usual and inevitable quota of duds.

But it's never as simple as saying "I want to make a film of such and such a book" and then having it happen. Money is difficult to raise these days as financiers want so many guarantees. Who is in the cast? Without a couple of "names" it's almost impossible for any project to move forward. Are sales lined up around the world? Very difficult to do this before the film is made and often the "name" actors and director are not valued enough to ensure upfront finance.

Cinema audiences around the world are (or are considered to be by distributors) aged 17-25. This limits the kinds of subjects that find favour with investors, who tend to believe their young audience wants nothing but action films, crude comedies, sequels and adaptations of comic strips. It has become harder to find the money to make more personal or more mature films. If such films are financed at all it's invariably with bargain-basement budgets.

A further problem is that admiration for and knowledge of a number of Australian classic novels is not necessarily widespread. Certainly the word of their excellence has not reached all of those in charge of making financial decisions. Last year I wrote an adaptation of Henry Handel Richardson's three volume epic The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, a book so revered by literary critics that they often chastise directors for failing to film it. I didn't really expect potential investors to have read the novel (I'm not sure anyone but a few academics and myself have actually read it, rather than just praising it, since 1940 at the latest) but I did at least expect them to have heard of it — and of her, the author.

This was not the case. No one I spoke to on the subject had the faintest idea of what or who I was talking about. Not that such puzzlement is all that amazing these days. When preparing a film about Rachmaninoff I found few investors and producers to whom his name meant anything; and a few years ago when I was planning a film about Mahler a Hollywood studio executive said "What I can't understand is why you want to make a film about a nonentity".