ALTHOUGH IT'S OFTEN said that British politics is becoming more American - two main parties which are almost indistinguishable on many issues, both financed by influence-buying tycoons and pressure groups - there is still one great difference; and it's a matter of life and death. Every leading politician in the US, whether Republican or Democrat, supports capital punishment. In 1992, Bill Clinton broke off his prijmary campaign and hastened back to Arkansas to execute a brain-damaged black man, Rickey Ray Rector, solely to forestall any suspicion that he was ‘soft’. This time round, the champion killer among the candidates is the Texas Governor, George W. Bush, who takes great pride in the fact that his state accounts for one third of all executions in the US. Last week he granted a temporary reprieve to a man awaiting lethal injection, Ricky McGinn: no big deal, given how many others he sends to their deaths, but extraordinary enough to earn long cover stories in both Newsweek and The Economist.

ALTHOUGH IT'S OFTEN said that British politics is becoming more American - two main parties which are almost indistinguishable on many issues, both financed by influence-buying tycoons and pressure groups - there is still one great difference; and it's a matter of life and death. Every leading politician in the US, whether Republican or Democrat, supports capital punishment. In 1992, Bill Clinton broke off his prijmary campaign and hastened back to Arkansas to execute a brain-damaged black man, Rickey Ray Rector, solely to forestall any suspicion that he was ‘soft’. This time round, the champion killer among the candidates is the Texas Governor, George W. Bush, who takes great pride in the fact that his state accounts for one third of all executions in the US. Last week he granted a temporary reprieve to a man awaiting lethal injection, Ricky McGinn: no big deal, given how many others he sends to their deaths, but extraordinary enough to earn long cover stories in both Newsweek and The Economist.

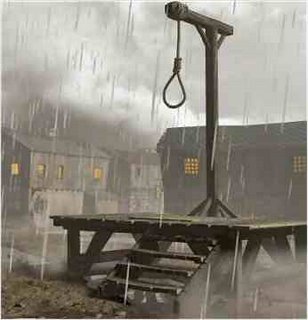

In Britain, by contrast, it us hard to find any politician who thinks we shall ever bring back hanging. Even William ‘Battling Billy’ Hague, who yearns for the return of the gallows, has admitted it’s a lost cause. ‘We have to be realistic,’ he says. ‘It is now highly unlikely that any Parliament would vote to bring back capital punishment.’ And yet, through surprisingly few people seem to know it, British judges are still condemning people to death. At 7 Downing Street, almost within earshot of Leo Blair’s nursery, the judicial committee of the privy council meets regularly to hear final appeals from prisoners on death row in Britain’s old Caribbean colonies.

A glance at Amnesty International’s annual report, published last week, shows the consequences of these deliberations. In Trinidad and Tobago, for instance, no fewer than nine men were hanged during one weekend in June last year. A tenth man was ‘hanged in July in violation of an order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights not to execute him until “such time as the court has considered the matter”. There were apparently eighty people on death row at the end of 1999. As the report’s preface points out, Amnesty International campaigns vigorously for the abolition of the death penalty. ‘Pending abolition,’ it adds, ‘AI calls on governments to commute death sentences, to introduce a moratorium on executions, to respect international standards restricting the scope of the death penalty and to ensure the most rigorous standards for fair trial in capital cases.’

This ought to make uncomfortable reading for Lord Hoffmann, a director of Amnesty International’s fund-raising arm. You may remember Hoffmann: he is the Law Lord whose vote in favour of extraditing General Pinochet was later annulled by five other Law Lords because his Amnesty links ‘were so strong that public confidence in the administration of justice would be shaken’. But he is also one of the privy council’s hanging judges, and in the last twenty months he has helped to send thirteen Caribbean prisoners to the gallows. One was Trevor Nathaniel Pennerman Fisher, a convicted murderer from the Bahamas who appealed to the privy council in October 1998, just one month before Hoffmann’s ruling against Pinochet. Fisher’s argument was simple: he should not be executed while a petition against his sentence was still being investigated by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), to which the government of the Bahamas is a party. Two judges, Lord Slynn and Lord Hope, agreed with him, stating that ‘it was hard to imagine a more obvious denial of human rights than to execute a man, after many months of waiting for the result, while his case was still under legitimate consideration by an international human rights body’. But they were outvoted by the three other judges – including milord Hoffmann of Amnesty International. Fisher was executed shortly afterwards.

It seems incredible that someone can be deprived of his life on a three to two split decision; you might as well decide his fate on a penalty shoot-out. But such verdicts have become increasingly common. Last December, again by a three to two vote, Hoffmann dismissed another appeal from the Bahamas. John Junior Higgs and David Mitchell, convicted murderers, pointed out that each of them had a petition pending before the IACHR – though after the Fisher decision their lawyers must have guessed that this wouldn’t impress Hoffmann and Co. But there was a second ground for appeal. Higgs and Mitchell said that their long confinement in one tiny, unsanitary and unfurnished cell, from which they were let out for only twenty-five minutes’ exercise four days a week, constituted ‘cruel and unusual punishment’, thus violating the principle that a man condemned to hang should not suffer further cruelties. (Higgs claimed that he has also been subjected to a ‘mock execution’ in 1997.) In the words of Lord Steyn, one of the dissenting judges: ‘The conditions in which the appellants were held for the last three years were an affront to the most elementary standards of decency. The Bahamas had, over a long period, treated them as subhuman and had forfeited the right to carry out the death sentences.’ Lord Cooke said that the men’s treatment in jail was ‘completely unacceptable in a civilized society’.

This is pretty strong language for senior judges to use. But Lord Hoffmann was unmoved by his colleagues’ bleeding-heart whimperings, ruling that ‘it would create uncertainty and be detrimental to the administration of justice in the Bahamas’ if the privy council started bothering about whether local prison conditions were ‘inhuman’. Perhaps he’d better skip the bit in Amnesty’s latest report that details just how appalling they are.

David Mitchell was hanged three weeks later, on 6 January 2000. John Junior Higgs cheated the gallows by committing suicide the previous day. He left a note thanking his warder for ‘turning a blind eye’ while he slashed his wrists.

Guardian 14 June 2000