I was speaking with Jack Benny the other day and he toldme about working with Ernst Lubitsch. The director had called Benny in 1939 and asked if he'd be available to do a film. "I said, 'I'll do it!' And he said, 'But you haven't read the script?' And I said, 'I don't have to read the script. If you want me for a picture, I want to be in it!' I'd have been an idiot to say anything else. It was always impossible for comedians like me or Hope to get a good director for a movie – that's why we made lousy movies – and here was Ernst Lubitsch, for God's sake, calling to ask if I'd do a picture with him. Who cares what the script is!"

I was speaking with Jack Benny the other day and he toldme about working with Ernst Lubitsch. The director had called Benny in 1939 and asked if he'd be available to do a film. "I said, 'I'll do it!' And he said, 'But you haven't read the script?' And I said, 'I don't have to read the script. If you want me for a picture, I want to be in it!' I'd have been an idiot to say anything else. It was always impossible for comedians like me or Hope to get a good director for a movie – that's why we made lousy movies – and here was Ernst Lubitsch, for God's sake, calling to ask if I'd do a picture with him. Who cares what the script is!"

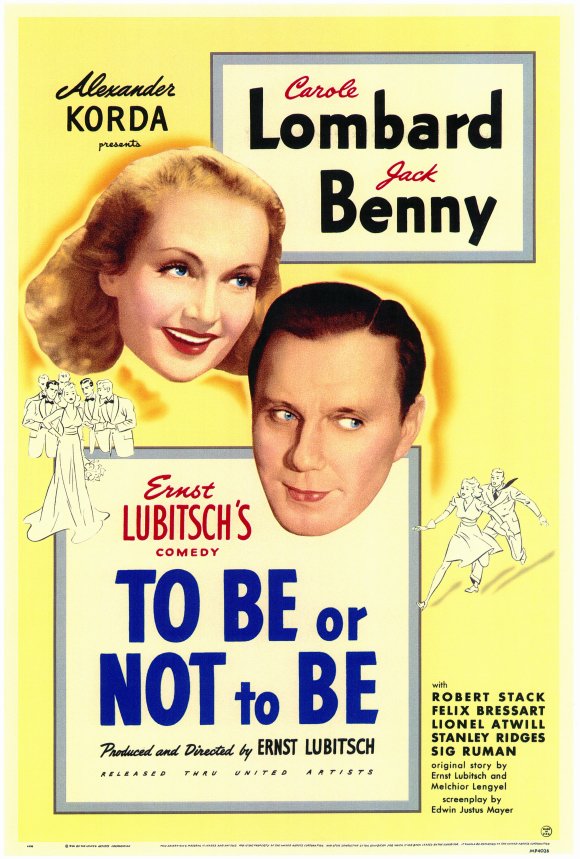

The film became To Be or Not To Be (Carole Lombard's last – she died in a plane crash before release) and it caused not a little controversy at the time for being a purportedly frivolous look at Nazism, dealing as it did with a troupe of Polish actors in occupied Warsaw and their comical confrontation with Hitler's gauleiters. But those who objected missed the point, having forgotten Thomas De Quincey's famous maxim: "If once a man indulges himself in murder, very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination." For Lubitsch, the Nazis' most damning sin was their bad manners, and To Be or Not To Be survives not only as satire but as a glorification of man's indomitable good spirits in the face of disaster – survives in a way that many more serious and high-toned works about the war do not. Lubitsch had a habit of establishing his European locales by showing a series of stores, each featuring a more unpronounceable name on its façade. He does this in To Be or Not To Be, then follows it with an identical sequence of the same shops as they looked after the bombing. The simplicity of this is deeply affecting, especially realizing the significance it must have held for Lubitsch, who was, after all, a European and to whom those "funny" names – like his own – meant more than the easy laugh he enjoyed giving his American audiences.

"The Lubitsch Touch" – it was as famous a monicker as Hitchcock's "Master of Suspense" – but perhaps not as superficial. The phrase does connote something light, strangely indefinable, yet nonetheless tangible, and seeing Lubitsch films – more than in almost any other director's work – one can feel this spirit; not only in the tactful and impeccably appropriate placement of camera, the subtle economy of his plotting, the oblique dialogue which had a way of saying everything through indirection, but also – and particularly – in the performance of every single player, no matter how small the role. Jack Benny told me that Lubitsch would act out in detail exactly how he wanted something done – often broadly but always succinctly – knowing, the comedian said, that he would translate the direction into his own manner and make it work. Clearly, this must have been Lubitsch's method with all his actors because everyone in a Lubitsch movie – whether it's Benny or Gary Cooper, Lombard or Kay Francis, Maurice Chevalier or Don Ameche, Jeanette MacDonald or Claudette Colbert – performs in the same unmistakable style. Despite their individual personalities – and Lubitsch never stifled these – they are imbued with the director's private view of the world, which made them behave very differently than they did in other films.

This was, in its own way, inimitable – though Lubitsch has had many imitators through the years – yet none has succeeded in capturing the soul of that attitude, which is as difficult to describe as only the best styles are, because they come from some fine inner workings of the heart and mind and not from something as apparent as, for instance, a tendency to dwell on inanimate objects as counterpoint to his characters' machinations. Certainly Lubitsch was famous for holding on a closed door while some silent or barely overheard crisis played out within, or for observing his people in dumb show through closed windows. This was surely as much a part of his style as it was an indication of his sense of delicacy and good taste, the boundless affection and respect he had for the often flighty and frivolous men and women who played out their charades for us in his glorious comedies and musicals.

No, closer to the heart of it (but not the real secret, because that, I believe, died with him – as every great artist's secret does) was his miraculous ability to mock and celebrate both at once and to such perfection that it was never quite possible to tell where the satirizing ended and the glorification began – so inseparably were they combined in Lubitsch's attitude and manner. In Monte Carlo, alone in her train compartment, Jeanette MacDonald sings "Beyond the Blue Horizon" in that pseudo-operatic, sometimes not far from ludicrous way of hers, and you can feel right from the start that Lubitsch loves her not despite the fragility of her talent but because of it: her way of singing was something irrevocably linked to an era that would soon be dead and whose gentle beauties Lubitsch longed to preserve and to praise, though he could also transcend them. For while her singing may be dated (but see her in the Nelson Eddypictures she did and note the difference), Lubitsch's handling of the number is among the greatest of movie sequences. As she leans out the train window, her scarf wafting in the wind, she waves to the farmers along the countryside and they – in a magical display of art over reality – wave back and join in the chorus to her song. Of course, Lubitsch is making fun of it as much as he is having fun with it – indeed, it's this tension between his affection for those old-fashioned operetta forms and his awareness of their absurdity that gives his musicals such unpretentious charm, as well as a wise and pervasive wit. And he is never patronizing, either to his audience or to his characters, and when Miss MacDonald and the brittle and ingratiating Jack Buchanan sing a reprise of that song at the close of Monte Carlo – leaning together now from their train window – their fond wave to the people they pass can be enjoyed both for its innocenceand gaiety as for the deeper sense of farewell to old times that Lubitsch's ineffable touch imparts.

Of course, it follows that Lubitsch made the very best of musical movies – not just the first great one in the first full year of sound – The Love Parade (1929) – but also just the best period – Monte Carlo, The Smiling Lieutenant, One Hour with You, The Merry Widow: no one has quite equaled or surpassed their special glow. (I guess Singin' in the Rain, directed by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly and written by Comden and Green, is the best of the "modern" ones, and I love it, but really it's of another breed.) Truth to tell, no one even came close: the Astaire-Rogers shows of the Thirties – and I'm quite fond of Mark Sandrich's Top Hat and George Stevens' Swing Time – seem tawdry by comparison, and Rouben Mamoulian's Love Me Tonight – a forthright imitation of Lubitsch with his usual stars, Chevalier and MacDonald – though remembered fondly by many, looks pretty labored today next to the genuine article.

Lubitsch had a terrific impact on American movies. Jean Renoir was exaggerating only slightly when he told me recently, "Lubitsch invented the modern Hollywood," for his influence was felt, and continues to be, in the work of many of even the most individualistic directors. Hitchcock has admitted as much to me and a look at Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise and Hitchcock's To Catch A Thief (both plots deal with jewel thieves so the comparisons are easy) will reveal how well he learned, though each is distinctly the work of the man who signed it. Billy Wilder, who was a writer on a couple of Lubitsch films – including the marvelous Ninotchka – has madeseveral respectful forays into the world of Lubitsch, as have many others with less noteworthy results. Even two such distinctive film makers as Frank Borzage and Otto Preminger, directing pictures which Lubitsch only produced – Desire (Borzage), A Royal Scandal and That Lady in Ermine (Preminger) – found themselves almost entirely in the service of his unique attitudes, and these movies are certainly far more memorable for those qualities than for ones usually associated with their credited directors. (Actually, Lubitsch is credited for That Lady in Ermine, but this was a sentimental gesture since he suffered a fatal heart attack and only shot eight days of it before Preminger took over.)

Lubitsch brought a maturity to the handling of sex in pictures that was not dimmed by the dimness of the censors that took over in the early Thirties, because his method was so circuitous and light that he could get away with almost anything. And that was true in everything he did. No other director, for example, has managed to let a character talk directly to the audience (as Chevalier did in The Love Parade and One Hour with You) and pull it off. There is always something coy and studied in it, but Lubitsch managed just the right balance between reality and theatricality – making the most outrageous device seem natural and easy; his movies flowed effortlessly and though his hand was felt, even seen, it was never intrusive.

But finally, of course, it was another world; it's no coincidence that several of Lubitsch's films were set in mythical Ruritanian countries, and that those set in "real" places have the same fanciful quality. Lubitsch achieved what only the best artists can – a singular universe where he sets all the rules and behavior. As Jean Renoir said in a recent interview: "Reality may be very interesting, but a work of art must be a creation. If you copy nature without adding the influence of your own personality, it is not a work of art… Reality is merely a springboard for the artist... But the final result must not be reality. It must only be what the actors and the director or author of the film selected of reality to reveal." Lubitsch had his own way of putting it; he once told Garson Kanin, "I've been to Paris, France, and I've been to Paris, Paramount. I think I prefer Paris, Paramount…"

Lubitsch had also the unique ability to take the lightest of material and give it substance and resonance far beyond the subject. The Shop Around the Corner, a charming story of love and mistaken identities in a Budapest department store, becomes under Lubitsch's hand both a classic high comedy and a remarkably touching essay on human foibles and folly. Another movie, In the Good Old Summertime, and a stage musical, She Loves Me, both used the same story but they are to Lubitsch as George S. Kaufman is to Molière. The most profound expression of this particular aspect of his work is in Heaven Can Wait, which tells a ridiculously simple and unassuming story of one fairly insignificant man's life – from birth to death – which Lubitsch turns into a moving testament to the inherent beauty behind our daily frivolousness and vanity, our petty crises, our indiscretions, our deepest vulnerability. It is Lubitsch's "divine comedy," and no one has ever been more gentle or bemused by the weaknesses of humanity. When the hero of the picture dies behind (of course) a closed door, Lubitsch's camera slowly retreats to take in a ballroom, and an old waltz the man loved begins to play, and death has no dominion. No other image I can think of more aptly or more movingly conveys Lubitsch's generosity or tolerance: the man has died – long live man.

After Lubitsch's funeral in 1947, his friends Billy Wilder and William Wyler were walking sadly to their car. Finally, to break the silence, Wilder said, "No more Lubitsch," and Wyler answered, "Worse than that – no more Lubitsch films." The following year, the French director-critic, Jean-Georges Auriol, wrote a loving tribute that made the same point; titled "Chez Ernst," it can be found in Herman Weinberg's affectionate collection, The Lubitsch Touch (Dutton). After comparing the director's world to an especially fine restaurant where the food was perfect and the service meticulous, the piece ends this way: "How can a child who cries at the end of the summer holidays be comforted? He can be told that another summer will come, which will be equally wonderful. But he cries even more at this, not knowing how to explain that he won't be the same child again. Certainly Lubitsch's public is as sentimental as this child; and it knows quite well that 'Ernst's' is closed on account of death. This particular restaurant will never be open again."