Dog owners are subs, inadequates, underachieving bullies. You’ve seen the stunted, bloated, pallid army of the potato fed, the army whose weapons are ambulatory ones. It is not by chance that such publications as Our dogs, Dogs Monthly and Dog World are to be found on newsagents’ shelves immediately beside Gung Ho and Guns and Ammo: corner shop Patels know all too well in lieu of what these pavement tyrants have dogs though were handguns licensed they’d of course deploy them as well as their dogs. Meanwhile for rottweiler read Colt, for alsatian Smith and Wesson, for great dane Walther, for dobermann some particularly lethal cross bow already available under plain wrapper.

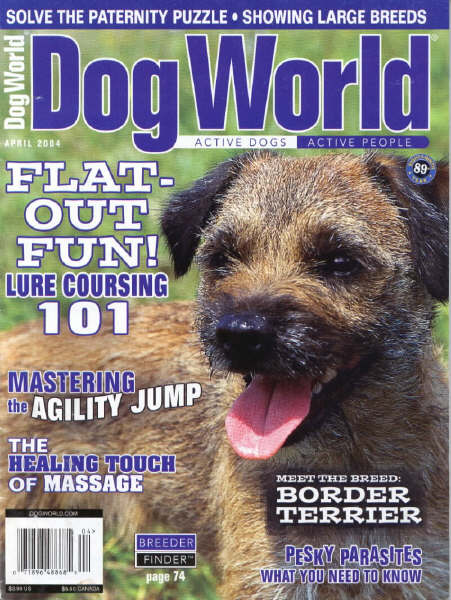

Dog owners are subs, inadequates, underachieving bullies. You’ve seen the stunted, bloated, pallid army of the potato fed, the army whose weapons are ambulatory ones. It is not by chance that such publications as Our dogs, Dogs Monthly and Dog World are to be found on newsagents’ shelves immediately beside Gung Ho and Guns and Ammo: corner shop Patels know all too well in lieu of what these pavement tyrants have dogs though were handguns licensed they’d of course deploy them as well as their dogs. Meanwhile for rottweiler read Colt, for alsatian Smith and Wesson, for great dane Walther, for dobermann some particularly lethal cross bow already available under plain wrapper.

They’re versatile instruments of self-assertion, dogs. They bite bits out of adults’ legs and children’s heads; they menace anyone with their bark and growl; they move at speed through public places. Best of all they dump their excrement everywhere. You wretched subs can’t go out on the street and shit, but your dogs can, and they do, don’t they, everywhere, with promiscuous abandon, and the beauty of it is that this is the bit that’s really nasty - these faeces can blind a child. Look at a rottweiler, look at its ostentatious convex anus, it tells you that this is simply a machine for turning Pal or Chum or Beta Brutus into a coiled cloacal mass. Of course rottweilers are good for biting and all purpose aggravation as well, otherwise they could be dispensed with and the sub could merely buy a can of Pal, open it in the street and dump it quivering in its marrowbone jelly on the pavement, thus achieving a brown coil of unusually great circumference for the world to step in. The manufacturers of Chum, Pedigree, Mowbray (whose factory I was once directed to by a local wag of whom I enquired the way to the best pie shop in that pie town), are the part-sponsors of something called a Poop Scoop Project. In an act of hypocritical beneficence, analogous with those of tobacco firms who sponsor lung cancer research, they have given almost half a million plastic trowels to councils tardily worried about the filth dogs leave behind them. The very name of the project, euphemistically cute, mitigates the nastiness and scope of the faecal menace; doggiewoggie wanna go poopywoopy dud oo didums. No one should be conned by Messrs Chum’s apparent philanthropy.

Chum flogs itself with devices that reveal that it knows all too well what bits to aim for. The advertisements appeal to the covert, unadmitted knowledge that the dog is a weapon and to the jolly, cretinous, British capacity for anthropomorphism. Chum refers to its 'breeder service’, whatever that is, as a friend of a friend’ -- the second friend being a golden retriever over whose head there hangs a hand in a position of benediction. This guff about man’s best friend is guff. Outside the work of Jack London it is only emotional cripples who enjoy friendships with dogs; and this ˜friendship’ is bought by the provision of food: Chum, say. Bribe your dog with our meat, otherwise he’ll turn on you, bite your limbs, shit on your doorstep. Man’s best friend is ever a tin of Chum away from being his best enemy. Friend into weapon in one easy step of omission.

The duality, the likelihood of the beast’s mutation from one state to the other, is more explicit, more threatening in Winalot’s current telly campaign. It shows, in a scene realised by computer cartoons, that if you fill a dog bowl with nuts and bolts you’re going to get a dog that’s robotic, a quadruped Ned Kelly, a machine. (That it should resemble the animatronic creature Archie in Lion comic in the late 50s merely signals the designer’s age.) Fill the bowl with Winalot and you get a golden retriever (evidently reckoned desirable, this back-of-Volvo breed). The machine would of course turn on its master, it’s an own goal of a dog. Winalot is a clever little film because its gag about this fear doesn’t for a second diminish the fear. And though it scotches the idea of the Winalot eater as a weapon, it has implanted that idea and that image. So you, the sub, are left with the vestigial notion that Winalot is associable, by the fact of its proximity, with biting out baby’s throat someone else’s baby, mind: all these ads are predicated on the hand (and family) that feeds not being bit. The endorsement of dog-faced people called ‘top breeders’, the promise of prolonged active life (i.e., goes on biting and dumping on pavements when long in the tooth), the shots of bounding beasts all these emphasise performance, belligerent potential, toughness. There’s a correspondence here with the associational gamut used to shift petrol, the fuel for another sort of closet weapon.

But advertisements for other products and services which use dogs ignore what is clearly their true appeal to their owners and don’t even acknowledge it in a 'coded’ fashion. The canine vigilante angle is nowhere to be found in, for instance, the half-witted anthropomorphism of British Telecom’s crass tableaux of animals speaking to each other on the phone if a monopoly must advertise, and that surely is moot, then it might at least do so with some style. And the ad with the dog that 'talks’ and proselytises on behalf of 'real fires’ (the things in grates, not pyromaniac’s delights) again exploits conformist, soft-old-pooch, canine lore. There is, then, a stereotypical dog-food dog (harsh, glossy, loyal on condition it’s fed right, hardly dissembling its brutality and excremental capacity) and there is a stereotypical loo-paper/telephone/family goods dog. There is virtually no affinity between the two. The stereotype that is closer to actuality is the former; the latter has something to do with the animals in Alison Uttley, with the tradition of bowdlerized, sanitized fairy tale. Proper fairy tales are stuffed with bad animals that eat humans: wily, deceitful animals that dissemble their savagery. It is to humans wittingly colluding with animals of just these qualities that Pal, Chum, Winalot and the rest have so deftly pitched their spiel.

1986