I'm always about the fifty millionth citizen of these inlands to latch on to any new cultural trend, but I must say I think I caught up with one at a dinner party the other night when it was seriously proposed that we should abandon the pleasures of the meal and of our own conversation in order to go out into the cold night and find a television set, because a programme was being shown which we all felt would be notably bad.

I'm always about the fifty millionth citizen of these inlands to latch on to any new cultural trend, but I must say I think I caught up with one at a dinner party the other night when it was seriously proposed that we should abandon the pleasures of the meal and of our own conversation in order to go out into the cold night and find a television set, because a programme was being shown which we all felt would be notably bad.

Suddenly I saw it all. It's badness that's the ultimate good in art and entertainment.

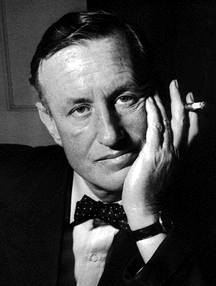

No doubt you grasped this a long time ago. But I could never understand why (for example) Ian Fleming's books engaged the public's imagination in a way that the books of even highly successful writers like Eric Ambler and John Le Carré have not. Was it really just the hero's superior taste in pearl cuff-links? Now I see, of course. Ambler and Le Carré make the mistake of writing very distinctive and compelling thrillers which actually thrill; Fleming had the sense to stick to rather feeble ones which don't.

Or take the bad old movies cult, which to my mind reaches its finest expression in the canonisation of W. C. Fields. Fields, as I now understand, is not great merely for the reasons which his admirers usually adduce - that he was mean, egocentric, drunken, and cruel to children. Wonderful as these attributes are, his real greatness is that as a comedian he had a marvellously limited range - from the bottom G of comedy down to about G flat, say - and all of it (in the films of his that I've seen) characterised by that same amateurish thinness which distinguishes Fleming.

There were other important movements which I had difficulty in understanding before, too. Like Pop Art. (Remember Pop Art, back in the dark days of 1964, when Britain stood alone, and income tax was 7/9d. in the pound?) Very importantly banal it was, as I now see.

And Cast-Off Clothes. (Remernber the Cast?Offs craze, back in the grim and gay hours of 1966, when the world still seemed new and hopeful, and Britain stood alone, and income tax was 8/3d. in the pound?) And for that matter Cast-Off Houses, and Cast-Off Junk to put in them (both still fashionable this year).

The great thing about this appreciation of badness for its own sake, I think, is that it reasserts the sovereignty of the individual in the face of the huge, impersonal forces which threaten him today (unlike in the days of Genghis Khan, the building of the Pyramids, or the Black Death, when the ordinary man could feel he was being enslaved or exterminated in a rather personal, meaningful way).

The point is that good art and good entertainment put the individual in an exposed position. By admitting, explicitly or implicitly, that one likes something because one thinks it's good, one lays bare one's tastes to criticism and possible ridicule. One reveals oneself. One may find that one's tastes are shared by people with whom it's socially or intellectually embarrassing to associate.

Imagine being seen to be deeply moved by a Beethoven symphony, or some other standard classic available on cheap records! (Imagine what it must have been like 60 years ago, when people performed the standard classics themselves at home. How could you make humorous remarks About "Your Tiny Hand is Frozen " when you were actually singing it?)

But a really sensitive man can embarrass himself almost as much in private by becoming completely absorbed in a bestseller. The point is not just that good art and good entertainment are more difficult to talk about and manage socially. It's that there's something demeaning about one's whole attitude towards them. One has, as it were, to put oneself at their feet and surrender to them.

Whereas with bad art and entertainment one can enjoy a much more relaxed relationship - a relationship in which one keeps the upper hand. Instead of standing there like a country bumpkin with one's mouth open, amazed that such skill and beauty can exist, or painfully anxious to know what deductions Fiedler will draw from Leamas's story, one can remain poised and cool. One can condescend a little, be amused at what the fashionable world/the young/the working classes are enjoying at the moment, even be a little amused at oneself for condescending, then move on without painful changes of loyalty to something else when the entertainment wears thin.

And one remains invulnerable, like a man who has the good sense never to fall in love. No one who sees "Diamonds Are Forever" face downwards on your coffee table is going to ask you incredulously if you actually like Ian Fleming. Of course you don't. No one does. No one supposes that anyone else does. It's a sort of joke.

Nor are people going to say, "Do you seriously love and admire that Early Victorian chamber-pot on your mantelpiece?" That's not what it's there for, as they well know. Your Early Victorian chamber-pot is like David Bailey's Pin-Ups, which are not, of course, intended as straightforward tributes to their subjects as Malcolm Muggeridge seems to think. They're offered complete with a fertile ambiguity of attitude on the management's part, which goes roughly:

"You can think these people are pretty if you like, or if you don't think they're pretty how about thinking they're amusing? And if that doesn't appeal to you, what we're trying to say is how amusing it is that some people might think they're pretty, only don't quote us on that, because what we really mean is that it's finding them amusing that's really so amusing, so the laugh's on you, and anyway we have other irons in the fire."

Well, as Omar Khayyam said, a Flask of Rather Amusingly Bad Wine, a Book of Bad Verse to Titter over, and a Dumb Girl Friend with a Placard round her Neck saying: "Don't think I'm a serious reflection on his taste in human relationships—I'm just a joke, for heaven's sake," and Wilderness is Paradise Enow.