Annotation by Richard Bleksley

Shining in the window a guitar that wasn't wood

It was looking like a silver coin from when they still were good

The man who kept the music shop was pleased to let me play

Although the price was twenty times what I could ever pay

Pick it up and feel the weight and weigh the feel

That thing is an authentic National Steel

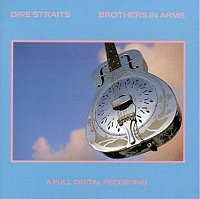

The National Steel guitar (if you haven’t seen Pete’s and want to know what one looks like, take a gander at the front cover of Dire Straits’ blockbusting Brothers in Arms album) is not to be confused with the steel guitar associated with country music. That instrument’s name comes from the steel bar (called a “steel”) used to stop the strings, whereas the body of the National is, literally, made of steel. Inside that body is a resonator, which acts much like a loudspeaker, making the instrument much louder than a normal acoustic guitar.

The National Reso-Phonic Guitar Company was founded in 1927 in Los Angeles. Although the guitars were originally intended for Hawaiian and jazz playing, they were quickly adopted by blues musicians, and have been indelibly associated with the blues ever since. Many bluesmen were itinerants, and their main sources of income were busking, and playing in the rough-and-tumble illegal bars known as jukes (word of unknown, possibly even African, origin, but hence “juke-box”) or barrelhouses (because the bar was often a plank supported by two barrels) frequented by black people in the South. In both situations, the National’s loudness was a distinct advantage: in the first instance, to draw in the punters; in the second, to cut through the racket of a Saturday night knees-up.

National guitars are still being made today, but genuine examples from before World War II, as played by many celebrated bluesmen, are rare and sought-after collectors’ items, commanding very high prices.

A lacy grille across the front and etchings on the back

But the welding sealed a box not even Bukka White could crack

I tuned it to an open chord, picked up the nickel slide

And bottlenecked a blues that sounded cold yet seemed to glide

Bukka White (1909? – 1977), real name Booker T. Washington White, is said to have detested the patronisingly primitive form of his name, but once it had appeared on a record label he was stuck with it. One of the most famous of National players, he specialised in the Mississippi Delta blues, that most “primitive” yet powerful form of the blues, his main inspiration being “the father of the Delta blues,” Charley Patton. (Oddly enough, the urbane and sophisticated B. B. King is his first cousin.) His best-known song is probably Fixin’ to Die, which was covered by Bob Dylan on his first album.

Never much of a commercial success in his youth, he was tracked down and “rediscovered” by blues enthusiasts in 1963, not having recorded for twenty years, and spent the rest of his life performing on the college and folk club circuit.

White was known for the ferocious way he attacked his music (“I play so rough – I stomp ’em – I don’t peddle ’em.”), hence “not even Bukka White could crack.”

Open chord – i.e. to tune the guitar so that when strummed with all the strings unstopped (open) a chord will sound. Normally done for:

Slide or bottleneck playing is a technique as old as the blues. The well-known story related by W. C. Handy, early populariser of the blues among white people and writer of St. Louis Blues, of how he first heard the blues in a deserted Mississippi railway station in 1903, has the ragged black musician playing the guitar flat on his lap and stopping the strings with a knife blade. The most common technique, though, was to slip a metal tube or the broken-off neck of a bottle over the little finger of the fretting hand and stop the strings with that, with the guitar held normally.

“Bent” or distorted notes are a defining characteristic of the blues, and, whatever instrument a bluesman plays, he will find some way of distorting the notes. In conventional guitar playing this is achieved by pushing the string sideways across the neck, but it is difficult to alter the pitch by much more than a semitone like this. With a slide it is possible to glissando up or down by an octave or more, always supposing the guitar will sustain the note for long enough. The result is a sort of melancholy wail or whine which is one of the most distinctive sounds of the blues.

With the advent of electric guitars, with their vastly increased sustain, bottleneck playing took on a whole new lease of life in the hands of such musicians as Elmore James and Muddy Waters. White players took it even further, with bravura displays by the likes of Johnny Winter and Duane Allman. The first British musician known to have employed the technique was Brian Jones, and his slide playing can be heard on the early Stones hits I Wanna Be Your Man and (better) Little Red Rooster.

The National Steel weaves a singing shroud

Just as sure as men in winter breathe a cloud

Scrapper Blackwell, Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Blake

Son House or any name you care to take

And from many a sad railroad, mine or mill

Lonnie Johnson's bitter tears are in there still

Francis “Scrapper” Blackwell (1903 – 1962) is in the curious position of his best-known records having been made accompanying someone else: the pianist and singer Leroy Carr. Furthermore, those records are somewhat neglected by modern blues enthusiasts, who tend to prefer their blues hard-edged and impassioned, whereas Carr’s and Blackwell’s duets were polished and urbane, with a mood of gentle melancholy, as in the celebrated How Long Blues (covered by Eric Clapton on his From the Cradle album).

Carr sang in a rich, clear voice and played a fairly simple piano, leaving the virtuoso stuff to his partner. Blackwell, whose skill at one-string lead playing rivalled that of Lonnie Johnson (see below), obliged, ornamenting the pauses between vocal lines with intricate solo fills, thus pioneering what has become a standard technique of the blues, especially amplified blues. And, no matter what modern tastes may think of their music, it appealed greatly to their contemporary audience. Between the two world wars the blues was black America’s pop music (something those who idealise the bluesman as a guitar toting hobo or a lonely sharecropper singing out his sorrows as he walks behind the plough tend to forget), and Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell were superstars, racking up one hit after another.

Blackwell took it very hard when Carr’s severe alcohol abuse killed him at an early age in 1935, and gave up music. He began to perform again in 1959, but was murdered in an Indianapolis alleyway three years later.

Blind Boy Fuller (1908 – 1941), real name Fulton Allen, was the best known and most popular practitioner of the Piedmont style of blues, a lighter, more melodic form from around Georgia and the Carolinas characterised by a deft, ragtime-y, finger-picking guitar style, and a far cry from the driving rhythms and raw emotion of the Mississippi blues. Apart from the amazing dexterity of his guitar playing, he is probably best remembered for the song usually known as Keep on Truckin’ (his original title was Truckin’ My Blues Away), which has been covered by countless people, including Donovan on his first album, and which has given a phrase to the American language.

Fuller was one of the last of the best-selling country bluesmen (he recorded between 1935 and 1940), but still died in poverty.

Florida isn’t often cited as a hotbed of the blues, but that’s where Arthur “Blind” Blake (1893? – 1933?) came from. And that’s about all that is known about him, save that he was a master of the finger-picked ragtime guitar. His record advertisements used to refer to his “piano sounding guitar,” such was the intricacy of his playing, which he applied to a wide range of material from blues to ragtime and novelty numbers.

Son House (1902 – 1988), real name Eddie James House Jnr., is called “the father of the Delta blues” as often as Charley Patton, with whom he played in his youth. In his turn he was musical mentor to two of the greatest bluesmen of all time, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. House was no virtuoso guitarist, but made up for it with the fierce intensity and passion with which he performed his music, perhaps the ultimate distillation of the pure Delta blues.

Like Bukka White, House was tracked down by enthusiasts in the sixties (1964 in his case), and began a new career playing to young white audiences until ill-health forced him to retire in the early seventies.

Alonzo “Lonnie” Johnson (1894 – 1970) is another bluesman whose modern reputation suffers because of the unfashionable urbanity of his style – indeed, he has been accused of going beyond urbanity and sinking into sentimentality. Well, perhaps, despite the commercial success of his blues recordings, his heart wasn’t really in it.

Coming from a comparatively sophisticated urban background, blues was only one of his musical accomplishments; but blues was what the record companies believed the “race” market (as it was known then) wanted, so Johnson was stuck with the bluesman label rather like Booker White was stuck with “Bukka.” He himself said that he would rather be remembered for his guitar playing.

And with good reason. Johnson was good enough to hold his own in such exalted company as the bands of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, and made a famous series of duet recordings with the white jazz guitarist Eddie Lang. As pioneer of the single-string run, later developed by Django Reinhardt (no relation to Patrick E.) and Charlie Christian, he can be fairly said to have invented the guitar solo as we know it.

He was widely admired by other musicians. Robert Johnson, generally held to be the greatest of all pre-war bluesmen, held him in such high esteem that he was known to claim to be related (he wasn’t). And, over in Britain after the war, a young banjo player in Chris Barber’s Band by the name of Tony Donegan changed his first name in homage.

Be certain, said the man, of who you are

There are dead men still alive in that guitar

Back there the next morning half demented by desire

For that storybook assemblage of heavy plate and wire

I sold half the things I valued but I'll never count the cost

While I can pick a note like broken bracken in the frost

And I hear those fabled names becoming real

Every time I feel the weight or weigh the feel

Of the vanished years inside my National Steel